At the heart of this story are two pivotal figures: John Vincent Atanasoff, a professor of physics and mathematics, and Clifford Berry, a physics graduate student and electrical engineering alumnus. Their collaboration led to the creation of the Atanasoff-Berry Computer (ABC), the world’s first electronic digital computer. The inception of ABC began with Atanasoff’s desire to hire an electrical engineering student, which led him to meet Berry through a recommendation from professor Harold W. Anderson.

The Atanasoff-Berry Computer

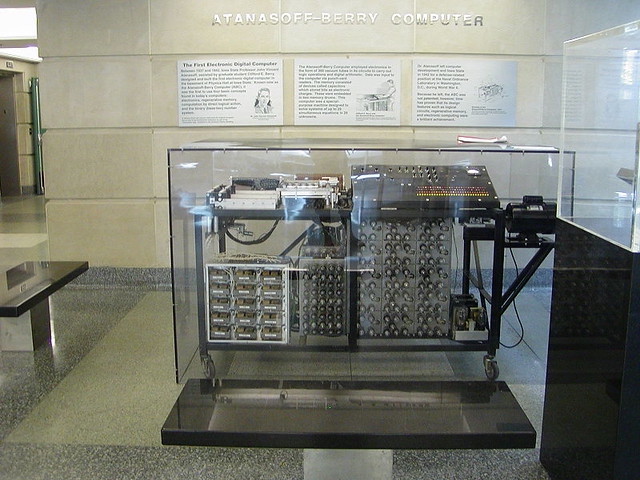

The ABC, built between 1937 and 1942 at Iowa State University, was a far cry from today’s sleek devices. It resembled a large desk, weighing around 750 pounds, and incorporated rotating drums for memory, vacuum tubes glowing with promise, and a unique read/write system that etched numbers onto cards with burn marks.

Despite its primitive appearance, the ABC was revolutionary. It was the first machine to implement features that are now staples of modern computers:

The ABC’s journey wasn’t without its controversies. When World War II interrupted their work, both Atanasoff and Berry moved on to other endeavors. Meanwhile, J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, developers of the ENIAC machine at the University of Pennsylvania, received the first patent for an electronic digital computer.

However, in 1973, a significant legal decision by U.S. District Judge Earl R. Larson overturned the ENIAC patents, acknowledging Atanasoff’s foundational work. This recognition was further cemented when President George Bush awarded Atanasoff the National Medal of Technology in 1990. Unfortunately, Berry had passed away in 1963, not living to see this vindication.

The ABC’s original structure was dismantled in the late 1940s and nearly lost to history. However, in 1997, a team from Iowa State and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames National Laboratory reconstructed a replica of the ABC. This painstaking process, involving researchers, engineers, and students, cost $350,000 and took four years.

Today, the replica resides at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, serving as a testament to the ABC’s groundbreaking role in computing history. This project not only preserved the physical legacy of the ABC but also reignited interest in the early days of computing.

The Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), developed during World War II and completed in 1945, is often hailed as the first general-purpose electronic digital computer. It marked a significant leap in computing capabilities and laid the groundwork for future developments.

Designed and built at the University of Pennsylvania by J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, the ENIAC was originally intended for artillery trajectory calculations for the U.S. Army. It was a mammoth machine, weighing about 30 tons and containing over 18,000 vacuum tubes, 70,000 resistors, and 10,000 capacitors.

The ENIAC’s development signified the transition from mechanical to electronic computing. While it was a far cry from modern computers in terms of size and user-friendliness, its design principles and electronic foundation influenced subsequent generations of computers. The ENIAC’s legacy is evident in its influence on later computers like the UNIVAC, also developed by Eckert and Mauchly.

The Colossus, developed by British codebreakers during World War II, was a pioneering computer used for cryptanalysis. Although its existence was a closely guarded secret for decades, the Colossus played a crucial role in deciphering German communications.

Developed at Bletchley Park, UK, the Colossus was designed to break the Lorenz cipher, used by the German High Command. It was the brainchild of engineer Tommy Flowers, who proposed using electronic valves (vacuum tubes) to speed up code-breaking tasks.

The Colossus remained a secret until the 1970s. Its contributions to the war effort and the field of computing were immense. It laid foundations for the development of electronic, programmable systems, influencing the design of future computers. The Colossus is a testament to the crucial role of computing in information security and intelligence.

The Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine, also known as the Manchester Baby, was a milestone in computer history. Built in 1948, it was the first computer to store both its program and data in electronic memory.

Developed at the University of Manchester in England by Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn, and Geoff Tootill, the Manchester Baby was initially a testbed for the innovative Williams-Kilburn tube, an early form of computer memory.

The Manchester Baby’s successful demonstration of the stored-program concept was a pivotal moment in computing, influencing the design of future computers. It led to the development of the Ferranti Mark 1, the world’s first commercially available general-purpose computer. The Manchester Baby thus holds a special place in computing history, representing a key step towards modern computing architectures.